Enter the Hand Shop

The Hand Shop

Cameron Conaway Jan 14, 2011

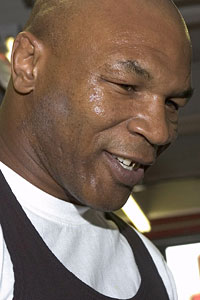

Cus

D’Amato’s Boxing Gym | C. Conaway/Sherdog.com

CATSKILL, N.Y. -- The gym’s walls breathe history. The yellowed and wrinkled newspaper clippings taped to every square inch tell a story of pride, triumph and setback.

On the surface, this gym looks no different than any other boxing gym. The heavybags are lopsided and duct-taped. Boxers of various skill levels and training intensities coalesce. This gym sounds no different than any other boxing gym. An old beat-up radio bangs out old beats. There are the three-minute buzzers and the grunts and the background pitter-patter music of speedbags. The gym smells no different than any other boxing gym -- the musty, rustic smell of wet handwraps, worn-out leather and hardwood floors that contain within them generations of sweat.

Advertisement

What’s in a name? Nothing. Shakespeare’s Juliet would agree. What’s behind a name? Everything.

We MMA fans are used to watching our sport on pay-per-view. We

order UFC events from home, oftentimes splitting the cost with a

group of friends. We head out to Hooters or Applebee’s when they

carry a card. In fact, for UFC 121 “Lesnar vs. Velasquez” on Oct.

23, an estimated 1,050,000 of us shelled out the $44.95 necessary

to purchase the event. It’s almost 2011, and MMA continues to boom.

It seems on top of the world. Yet, nearly 20 years ago, a single

man named Mike Tyson generated 200,000 more pay-per-view buys than

UFC 121 for his fight against Donovan “Razor” Ruddock.

When young MMA fighters are asked how they became involved in the sport, it has almost become a cliché that they bring up the legendary heroics of Royce Gracie during his UFC reign from 1993-94. Many MMA fans see this as the beginning of the cultural popularization of fighting. However, it was in 1985 that a 19-year-old Tyson helped take fighting from being a niche spectator sport to a mainstream media obsession. MMA fans cheer when a Randy Couture or Frankie Edgar highlight makes it on ESPN SportsCenter’s “Plays of the Week.” But Tyson highlights were shown years before and on a regular basis. And they are still shown. He was considered by most to be “the baddest man on the planet.”

Thierry

Gourjon/Splash News

The intention here is not to counter MMA’s recent success but to set the framework and paint a larger picture of the fight game than is usually discussed. As a little boy, some of my earliest memories of fighting are of the crowds of adults that would gather in the garage of my best friend’s father’s house to watch Tyson fights. These adults would not show up until very late at night, usually 30 minutes before Tyson’s bout was to air. The undercard did not matter, as it involved regular boxers boxing. Tyson was a phenomenon. People even wanted to show up early to the fights just to catch the pre-fight-hype training montage of Tyson bobbing and weaving and tenaciously working the heavybags with blurring speed.

Those training videos were shot in Cus D’Amato’s Boxing Gym. In November, I was granted access to tour the gym, interview the trainers and even get some one-on-one training.

For many fight fans, their first introduction to combat sports came not through Royce Gracie but through the sport of boxing -- be it the days of Muhammad Ali or George Foreman or Tyson. So when I found myself needing to pass through Catskill, N.Y., for a business trip, my subconscious registered something long before my conscious mind. “Catskill,” I thought to myself. “I feel I know Catskill, even though I’ve never been there.” A bit of research led me to the reason: Catskill is the home to the world-renowned Cus D’Amato Boxing Gym. It is where, at just 14 years old, Floyd Patterson trained to then, at age 17, win the gold medal at the 1952 Olympic Games. Then, at the age of 21 and in the wake of Rocky Marciano’s retirement, Patterson beat Archie Moore to become the youngest man to win the world heavyweight championship; he later became the first to regain it. He was the first Olympic gold medalist to win a professional heavyweight title. Patterson was trained by Cus D’Amato, a man who quickly became known as much for his technical boxing knowledge as for his passion and generosity and his willingness to become a father figure and positive role model to the Catskill community youth who entered his gym.

“Floyd Patterson was the first fighter in history to net a million-dollar purse,” said Kevin Rooney, who won the 147-pound sub-novice New York Golden Gloves championship at Madison Square Garden in 1975 and then packed up his life to train under D’Amato. He later became Tyson’s chief trainer (1985-88).

In the initial thirty minutes of my interview with Rooney, I learned that many firsts happened in this gym. I was astonished, especially considering the conversation had yet to include Tyson’s name. Mike Tyson entered the Cus D’Amato Boxing Gym in 1979. He was a 13-year-old boy with very little, if any, familial support, destined for the type of imprisoned or buried future so typical for youth without any guidance in life.

“When he came in here, he was already close to 200 pounds of pure muscle,” said Rooney, “and this was before he had ever lifted a weight in his life. What we did was take the genetics and add to it what we believed was the best boxing techniques in the world. On top of that, Cus served as Mike’s constant mentor. He was Mike’s life coach. It was the perfect recipe for success.

“During Mike’s first week here, Cus had him do some light sparring with a veteran boxer just so Cus could see how Mike moved,” Rooney added. “He knew the veteran boxer was good enough to spar safely, to test anybody who entered the ring with him. However, the vet put a good whooping on Mike for two rounds, so much so that Cus immediately brought the sparring to an end. The veteran had to put that kind of whooping on Mike because Mike was relentless, coming forward, trapping, pressuring. The guy felt Mike’s power early and knew this 13-year-old could hurt him if he wasn’t careful.”

Rooney stood up from the bench and reenacted the scene between D’Amato and Tyson.

“That’s enough, Mike,” Rooney said while waving his arms. “Good work.”

Rooney moved to a new position and raised the pitch of his voice.

“C’mon,” he said, channeling Tyson, “give me one more round.”

“No, Mike. You’re done for now. I’ve seen enough. Out.”

“Then,” Rooney said dramatically, “as Mike got out of the ring, Cus turned to everyone in the gym and, in a way so unlike his usual self, pointed to Mike and announced to everybody: ‘There’s the next heavyweight champion of the world!’”

What Tyson loved was his ability to close the distance and explode with devastation. His hands were held in front of his face at nose level, rather than to the side as boxers were and still are taught. He simultaneously slipped punches by moving from side-to-side like a shark cutting through ocean waters, but he also used the momentum of this side-to-side motion to generate power for his punches. This style was efficiency at its finest, a constant synergy of defense and offense. A short heavyweight -- many reports say he was all of 5-foot-8 -- Tyson is the best example in boxing history of how a shorter boxer can take out a taller foe. The style he used is known as the “peek-a-boo” style. It was developed by D’Amato and is still taught in this gym.

D’Amato was the Greg Jackson of his time.

Continue Reading » Page Two: Old School vs. New School