Dana’s Dilemma

Todd Martin Jun 9, 2010

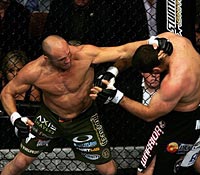

Chuck

Liddell’s return to MMA competition against Rich

Franklin at UFC

115 should have been a foregone conclusion. Liddell is one of

the UFC’s biggest drawing cards and he has made no secret of his

desire to continue fighting. Yet it was not a decision that came

easily for UFC President Dana White. The struggle with what to do

with aging legends like Liddell will present an increasingly

difficult dilemma for the UFC in the coming years.

Following Liddell’s loss to Mauricio “Shogun” Rua at UFC 97, his fourth loss in five fights (three via knockout), White was emphatic that Liddell would not fight again in the UFC.

“He’s a huge superstar, and we could still sell a lot of tickets

(with him),” White remarked at the post-fight news conference. “But

I don’t care about that. I care about him. I care about his health,

and it’s over, man. It’s over.”

White spoke in absolute terms on that evening and there’s no reason to doubt his sincerity, but Liddell’s retirement was short-lived. In fact, Liddell will end up taking less time off than a prime Quinton “Rampage” Jackson did between his fight against Keith Jardine at UFC 96 and his grudge match return against Rashad Evans at UFC 114.

Fighter Health

When White explained his reasons for wanting Liddell to retire, Liddell’s health was the primary concern. Liddell is 40 years old and has lived it up over the years more than most. His reflexes have been noticeably slower in recent fights and his once legendary chin no longer can hold up to the same punishment.

Watching the legend that held on too long is a sad scene in any sport. Older baseball fans lament Willie Mays’ days with the New York Mets and basketball fans wanted Michael Jordan to go out as NBA champion rather than missing the playoffs with the Washington Wizards. However, the predicament of the athlete holding on too long is most troubling in the context of combat sports.

Fighters don’t just risk their dignity when fighting at an advanced age. They risk their future quality of life. That example is most clearly visible in boxing, where over the years many great fighters have held on for way too long. The consequences of those decisions can be seen now, with brain-damaged boxers who struggle with speech when they should be enjoying the golden years of their lives.

This trend in boxing hasn’t just been bad for the boxers themselves; it has been bad for the sport itself. It casts a dark cloud over boxing and makes fans think about their complicity in tragedies they never wanted to see. It is important not only for the fighters themselves but also for the sport that in 20 years there aren’t a litany of ex-MMA stars who show obvious physical and neurological effects of their wars in the cage.

UFC is keenly aware of this fact. Many of the key figures in the company come from a boxing background, and White has been emphatic that he wants to avoid making the same mistakes that boxing did.

To this end, the UFC has shown a willingness to release star fighters that the company no longer feels can compete at the top level. Mark Coleman was cut after a main event with Randy Couture. Ken Shamrock wasn’t given another UFC fight despite setting the UFC’s buy rate record at the time and TV ratings record at the time in consecutive bouts.

Those moves reflect the UFC’s desire to not be a part of helping fighters continue on too long, but it’s not always clear when a fighter should retire for his own good. Many assumed Randy Couture was done as a top fighter at age 39 following losses to Josh Barnett and Ricco Rodriguez. Eight years and three championship title runs later, it’s clear that aging legends of the sport shouldn’t be underestimated. Asking them to stop also brings up additional problems.

Fighter Desire

While MMA promoters may feel they are doing the right thing when they refuse to book past-their-prime stars, the fighters themselves are extremely unlikely to sympathize with that position.

Athletes very often want to compete well past their physical primes. They love the challenge and don’t want to give up the competition that drives them. Additionally, there is a strong financial incentive to continue. Top stars know that they can make more in one or two additional fights than they can working a different job for the next 10 years.

Non-fighters can try their hardest to convince a fighter that he should stop fighting for his own health, but ultimately who are we to tell them what to do? Even if a promoter or fan is well intentioned, there is something paternalistic and disrespectful about telling a legend when to hang it up.

Fighters like Antonio Rodrigo Nogueira and Wanderlei Silva have taken tremendous punishment in recent years. But after all they have accomplished in the sport, they ought to have the dignity of deciding when to call it quits. Of course, they may want to go another 15 years and may react with hostility to anyone who suggests otherwise.

The situation is additionally complicated with White and Liddell because of the close relationship between the two over the years. White wants what is best for Liddell, but at the end of the day it’s difficult to justify deciding that you know better than another grown man what he ought to do with his own life.

Money

While the conflict between a fighter’s health and his personal interests is not easily resolved, there’s another huge factor at play when it comes to aging MMA legends. The millions of dollars involved are no small matter.

Liddell is still an enormous box office attraction. His last fight did a reported 650,000 buys on pay-per-view. Since the UFC PPV boom of 2006, none of Liddell’s seven fights has drawn south of 475,000 buys. He is a proven drawing card against big names and relative unknowns alike. Liddell’s return against Franklin will net the UFC millions of dollars in revenue.

At the end of the day, sports leagues are driven by money. Older stars are driven out of team sports because they no longer can play well enough to justify large salaries. The team will struggle and revenues will go down. Athletes are left with the choice of retiring or continuing for a fraction of the salary they used to make.

This dynamic is completely different in fighting. Older fighters don’t have to compete over the course of a season against the best competitors in the world. They can be matched up with easier opponents to get them wins, and they can continue to bring in huge revenues based on the force of their personality and reputation. There eventually comes a point when a fighter has lost so many times that he can no longer draw, but that can take a very long time.

While the UFC is of course a business and wants the money that Liddell will bring in, the company can lose a few Liddell paydays and still be just fine. But there is an additional problem for the UFC if it releases stars like Liddell: the competition.

The UFC right now has a stronghold on MMA worldwide, and it has moved aggressively to prevent serious competition from rising up. If Liddell loses to Franklin and the UFC decides to stop using him, there will be a host of MMA promotions lining up to take Liddell.

A star the magnitude of Liddell is precisely the sort of game changer that could alter Strikeforce’s position in the MMA landscape. That’s obviously something White doesn’t want to see, and retaining stars like Liddell and Tito Ortiz is perhaps as much about keeping them from the opposition as retaining them for the UFC.

The question remains as to what the UFC should ultimately do with aging stars who want to continue to fight. Ultimately, there are no easy solutions. If you keep giving Liddell fights, you end up being criticized as a heartless promoter exploiting a broken-down star. If you let him go, you lose revenue, help the opposition and likely won’t even have the desired effect of preserving the man’s health. All you receive is the ability to say your hands were clean. Sometimes, it’s not so easy being a promoter.

Todd Martin has covered MMA for CBSSports.com, SI.com and the Los Angeles Times. He is a licensed attorney in the state of California.

Following Liddell’s loss to Mauricio “Shogun” Rua at UFC 97, his fourth loss in five fights (three via knockout), White was emphatic that Liddell would not fight again in the UFC.

Advertisement

White spoke in absolute terms on that evening and there’s no reason to doubt his sincerity, but Liddell’s retirement was short-lived. In fact, Liddell will end up taking less time off than a prime Quinton “Rampage” Jackson did between his fight against Keith Jardine at UFC 96 and his grudge match return against Rashad Evans at UFC 114.

The turnaround on Liddell reflects a variety of conflicting factors

when it comes to handling the careers of older fighters. It’s a

predicament with downsides no matter what course the UFC takes, and

the problem will only become greater in the coming years as more

stars of the post-2006 UFC pay-per-view boom period grow older.

Fighter Health

When White explained his reasons for wanting Liddell to retire, Liddell’s health was the primary concern. Liddell is 40 years old and has lived it up over the years more than most. His reflexes have been noticeably slower in recent fights and his once legendary chin no longer can hold up to the same punishment.

Watching the legend that held on too long is a sad scene in any sport. Older baseball fans lament Willie Mays’ days with the New York Mets and basketball fans wanted Michael Jordan to go out as NBA champion rather than missing the playoffs with the Washington Wizards. However, the predicament of the athlete holding on too long is most troubling in the context of combat sports.

Fighters don’t just risk their dignity when fighting at an advanced age. They risk their future quality of life. That example is most clearly visible in boxing, where over the years many great fighters have held on for way too long. The consequences of those decisions can be seen now, with brain-damaged boxers who struggle with speech when they should be enjoying the golden years of their lives.

This trend in boxing hasn’t just been bad for the boxers themselves; it has been bad for the sport itself. It casts a dark cloud over boxing and makes fans think about their complicity in tragedies they never wanted to see. It is important not only for the fighters themselves but also for the sport that in 20 years there aren’t a litany of ex-MMA stars who show obvious physical and neurological effects of their wars in the cage.

UFC is keenly aware of this fact. Many of the key figures in the company come from a boxing background, and White has been emphatic that he wants to avoid making the same mistakes that boxing did.

To this end, the UFC has shown a willingness to release star fighters that the company no longer feels can compete at the top level. Mark Coleman was cut after a main event with Randy Couture. Ken Shamrock wasn’t given another UFC fight despite setting the UFC’s buy rate record at the time and TV ratings record at the time in consecutive bouts.

Those moves reflect the UFC’s desire to not be a part of helping fighters continue on too long, but it’s not always clear when a fighter should retire for his own good. Many assumed Randy Couture was done as a top fighter at age 39 following losses to Josh Barnett and Ricco Rodriguez. Eight years and three championship title runs later, it’s clear that aging legends of the sport shouldn’t be underestimated. Asking them to stop also brings up additional problems.

Fighter Desire

While MMA promoters may feel they are doing the right thing when they refuse to book past-their-prime stars, the fighters themselves are extremely unlikely to sympathize with that position.

Athletes very often want to compete well past their physical primes. They love the challenge and don’t want to give up the competition that drives them. Additionally, there is a strong financial incentive to continue. Top stars know that they can make more in one or two additional fights than they can working a different job for the next 10 years.

Non-fighters can try their hardest to convince a fighter that he should stop fighting for his own health, but ultimately who are we to tell them what to do? Even if a promoter or fan is well intentioned, there is something paternalistic and disrespectful about telling a legend when to hang it up.

Fighters like Antonio Rodrigo Nogueira and Wanderlei Silva have taken tremendous punishment in recent years. But after all they have accomplished in the sport, they ought to have the dignity of deciding when to call it quits. Of course, they may want to go another 15 years and may react with hostility to anyone who suggests otherwise.

The situation is additionally complicated with White and Liddell because of the close relationship between the two over the years. White wants what is best for Liddell, but at the end of the day it’s difficult to justify deciding that you know better than another grown man what he ought to do with his own life.

Money

While the conflict between a fighter’s health and his personal interests is not easily resolved, there’s another huge factor at play when it comes to aging MMA legends. The millions of dollars involved are no small matter.

Liddell is still an enormous box office attraction. His last fight did a reported 650,000 buys on pay-per-view. Since the UFC PPV boom of 2006, none of Liddell’s seven fights has drawn south of 475,000 buys. He is a proven drawing card against big names and relative unknowns alike. Liddell’s return against Franklin will net the UFC millions of dollars in revenue.

At the end of the day, sports leagues are driven by money. Older stars are driven out of team sports because they no longer can play well enough to justify large salaries. The team will struggle and revenues will go down. Athletes are left with the choice of retiring or continuing for a fraction of the salary they used to make.

This dynamic is completely different in fighting. Older fighters don’t have to compete over the course of a season against the best competitors in the world. They can be matched up with easier opponents to get them wins, and they can continue to bring in huge revenues based on the force of their personality and reputation. There eventually comes a point when a fighter has lost so many times that he can no longer draw, but that can take a very long time.

While the UFC is of course a business and wants the money that Liddell will bring in, the company can lose a few Liddell paydays and still be just fine. But there is an additional problem for the UFC if it releases stars like Liddell: the competition.

The UFC right now has a stronghold on MMA worldwide, and it has moved aggressively to prevent serious competition from rising up. If Liddell loses to Franklin and the UFC decides to stop using him, there will be a host of MMA promotions lining up to take Liddell.

A star the magnitude of Liddell is precisely the sort of game changer that could alter Strikeforce’s position in the MMA landscape. That’s obviously something White doesn’t want to see, and retaining stars like Liddell and Tito Ortiz is perhaps as much about keeping them from the opposition as retaining them for the UFC.

The question remains as to what the UFC should ultimately do with aging stars who want to continue to fight. Ultimately, there are no easy solutions. If you keep giving Liddell fights, you end up being criticized as a heartless promoter exploiting a broken-down star. If you let him go, you lose revenue, help the opposition and likely won’t even have the desired effect of preserving the man’s health. All you receive is the ability to say your hands were clean. Sometimes, it’s not so easy being a promoter.

Todd Martin has covered MMA for CBSSports.com, SI.com and the Los Angeles Times. He is a licensed attorney in the state of California.

Related Articles