How a UFC Impostor Became Australia’s First NHB Event

This is the third installment of a multi-part series on the

first modern MMA show held in Australia, billed the “Australasian

Ultimate Fighting Championship.”

PROLOGUE |

PART 1 |

PART 2 |

PART 3 |

PART 4 |

PART 5

The day of the inaugural “Australasian Ultimate Fighting

Championship” in Sydney, nobody in Australia—least of all the

tabloid journalists—knew what to expect.

“The rules are there are no rules,” declared Sydney’s Daily Telegraph. “Today some of the world’s best exponents of kung fu, karate, jiu-jitsu and other martial arts disciplines will enter the octagonal cage to decide who is the ‘ultimate fighter.’”

The image adorning the article exhibited an airborne Elvis Sinosic, who would make his NHB debut at the tournament, landing a sidekick on a stationary punching bag. Beneath his picture, the article listed Sperry’s record as 273-1. The Telegraph was not the only outlet to send an unassuming reporter to the center of Sydney to report back on the planned “ultimate fighting” tournament, the first of its kind in Oceania. The previous evening, it was given lengthy coverage on ABC Radio National’s “The Sports Factor,” which tried in earnest to explore the appeal of NHB while also featuring the by-now staple critic who equated ultimate fighting with the decline of modern civilization.

Alongside sound bites from a traditionalist karate instructor concerned with the “corruption” of martial arts principles and MMA exponents Frank Shamrock and Carlson Gracie Sr., who spoke to the history and evolution of NHB, American sports sociologist Don Sabo was given lengthy airtime. He used it to compare fighters to prostitutes and claim that NHB events acted “as a type of cultural gasoline” that “fan the flames of male aggression.”

“The first Australasian Ultimate Fighting championships kicks and head butts its way into Sydney tomorrow night,” concluded presenter Amanda Smith. “I think I might be washing my hair at that time.”

* * *

For first-time fight promoter Randy Bable, the tournament was far from a sure thing, even as the days leading up the event turned to hours.

One of the main draws in the bracket, enormous kickboxer Zane Frazier, who competed at UFC 1 and UFC 9, pulled out after tearing his calf muscle running on Bondi Beach. His replacement, self-taught grappler Neil Bodycote, had to scramble to get his shift working security at a Newcastle nightclub covered.

There was also the presence of the New South Wales Boxing Authority, which had not given its blessing for the event to move forward and would send a small battalion of uniformed police officers down to the harbor, ready to shut down the spectacle if the state-appointed commissioners did not like what they saw.

Plus, New York’s Semaphore Entertainment Group, which owned and operated the Ultimate Fighting Championship, threatened to go to court and seek an injunction shutting down the event on the grounds that Bable was infringing its trademarks and passing itself off as the UFC.

On top of all that, the faux octagon had not been properly reinforced, prompting fears that the fighters would fall through the canvas if last-minute modifications were not made.

“It was insane,” a grinning Bable recounted 24 years later. “It was crazy.”

Future UFC champion Frank Shamrock, one of the many historically significant MMA figures to be pulled into the orbit of Australia’s first-ever NHB show, knew this was not actually a UFC event, and he had questions.

“I was wondering how they were using the name and stuff,” Shamrock said, “but at the time, I was really just focusing on fighting and training. I was just excited to go to Australia and for the guys to compete. There was a good prize. It was one of those trips that I really enjoyed and was really looking forward to.”

* * *

As the head coach of the famed Lion’s Den, Shamrock put up Pancrase stalwart Vernon White and untested Matt Rocca as event participants. It was Shamrock’s job to oversee their preparation as well as corner the pair in Sydney. The role came with its share of perks, including staying at the Swiss Grand Hotel on Bondi Beach through fight week. The former King of Pancrase was well-received by the martial arts community, which came out in force for the tournament.

The event itself was preceded by approximately two months training at the Lion’s Den academy in Lodi, California, a precursor to today’s MMA super camps. The Lion’s Den model provided fighters with training, housing and meals in exchange for a cut of their earnings. With Ken Shamrock away making the transition to professional wrestling, the job of running the fight team fell largely to Frank.

“I didn’t have a lot of no holds barred experience at the time,” he said. “Back then, we had no information on anybody. Ken would send me into the dressing rooms of people competing. I would look at their outfits and listen to what they were saying. That was what our research was. It was so rudimentary it was ridiculous.”

Frank had high hopes for White, a fellow Pancrase competitor who was the second person inducted into the Lion’s Den stable in 1993. White was coming off of a finals appearance against Pedro Rizzo in an eight-man World Vale Tudo Championships tournament, and after three years as a pro fighter, he had claimed a deceiving 10-18-1 record, most of which fell under Pancrase’s modified rules in Japan. Having witnessed Australian fighters’ limited ground game on the Pancrase circuit, Shamrock figured White would easily outgrapple the locals or have the striking prowess needed to put out anyone on the feet.

The main focus of the fight camp in early 1997 was transitioning from open-hand strikes and rope escapes to the much less prescriptive world of NHB in a cage.

“We went from fighting in Pancrase to doing straight-out MMA, so in training, we couldn’t lay on our backs; you had to move, unless you wanted to get punched in the face,” White remembered. “Pancrase was way different. There was no punching in the face, open-hand only, unless somebody really pissed you off. Once we got into this, into MMA and NHB, there was no more making faces. You’d get your eyebrows punched off.”

Whereas White was an experienced competitor for the era, Rocca, his 20-year-old counterpart, was less than a year into his tenure at the Lion’s Den. Rocca carried the badge of “young boy,” a term denoting an entry-level position in the academy’s pecking order, with responsibility over the Den’s house chores.

“So much time is spent [in the Lion’s Den] trying to earn your stripes,” Rocca said. “You’re a young boy. You’re shaving your head. You’re taking on all of the menial tasks: washing, cleaning, groceries. There was this symbolism. You get the opportunity to cross over and become a fighter. I just wanted to seize the opportunity. I knew that going into the event there was going to be people in there with a lot more experience than me—in martial arts and also in life. I was 20 years old, and everything was going a million miles a minute.”

* * *

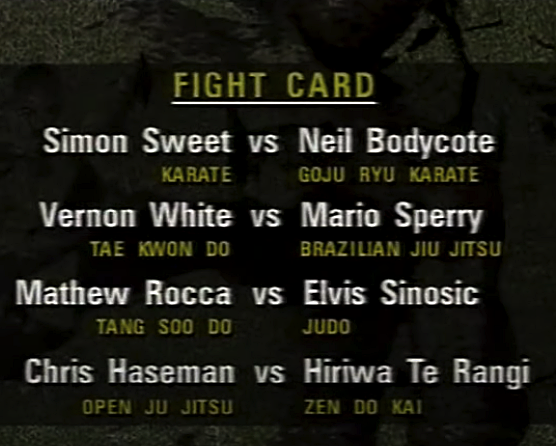

Originally signed as an alternate with a single bout on the undercard, Rocca was bumped up to the main bracket due to a succession of withdrawals. He was far from the only combatant who would make his debut that night. Of the five ANZACs on the card—Elvis Sinosic, Chris Haseman and Neil Bodycote hailed from different parts of Australia, while Hiriwa Te Rangi and Simon Sweet were kickboxers from New Zealand—only Haseman had NHB experience in the one-and-done “Martial Arts Reality Superfighting” event in Alabama the previous November.

Sperry also competed in the MARS event, taking home the MARS Superfight Championship, rightfully making him, White and Haseman the tournament favorites for people in the know.

In part, the Oceanic-centric nature of the roster was attributable to the withdrawal of UFC veterans Gerry Harris, Steve Jennum and Zane Frazier from the tournament, prompting Bable to call up each of his three alternates—Rocca, Sinosic and Bodycote—to the main bracket.

“There were people who knew what they were doing, and there were people who didn’t,” said Mark Castagnini, who commentated the event and was involved in promoting it through Blitz martial arts magazine, which he managed. Australian and New Zealand fighters “just wanted to test themselves against the best,” he continued. “Today, nobody fights in the UFC or gets into the cage unless they’re 100% ready. They’ve got high-performance coaching; they’ve got all of this knowledge. These blokes had nothing. They were just getting in there, seeing the bloke across from then and having a crack, hoping it would work out.”

The lineup was also impacted by the reluctance of some of Australia’s more experienced NHB exports, including Pancrase’s Larry Papadopoulos and Alex Cook, to take a risk on a new promotion.

“We were approached and asked if we wanted to fight,” said Papadopoulos, the most successful Australian who competed for the Japanese organization at the time. “Because we were kind of contracted with Pancrase, we asked the promotion if they were OK with it. After some hemming and hawing the Japanese promoters regarded us as their talent, so they asked us not to fight. It was something where it was an unproven promoter. We didn’t really know whether the event would take off, and therefore, we kind of held back. We said ‘not this one,’ and thought we’d see how it goes. That’s why I didn’t personally get involved.”

The circumspection of Papadopoulos, who would come to be involved in the event as a consultant to Bable and a cornerman to Bodycote, was apparently shared by many of Australia’s other big names in combat sports. Efforts to secure Adam Watt, at that time one of the country’s most highly regarded kickboxers, came to nothing. Similar approaches to eight-time world kickboxing champion Stan “The Man” Longinidis were apparently rebuffed on the understanding that conversations could resume if and when Bable geared up for the second tournament, then slated for October 1997.

* * *

Elite fighters were not the only people doing due diligence from the bleachers. According to Bable, the late Rene Rivkin, a famous Australian stockbroker who was convicted on insider trading charges in 2003, may have been interested in investing in the NHB startup. Rivkin had his assistant call looking to secure front-row seats a few days before the debut event. Bable tried and failed to land sponsors or investors in the early stages of setting up the tournament, and he rebuffed Rivkin’s request, saying the seats were sold-out while believing there would be opportunities to court investors after pulling off the event.

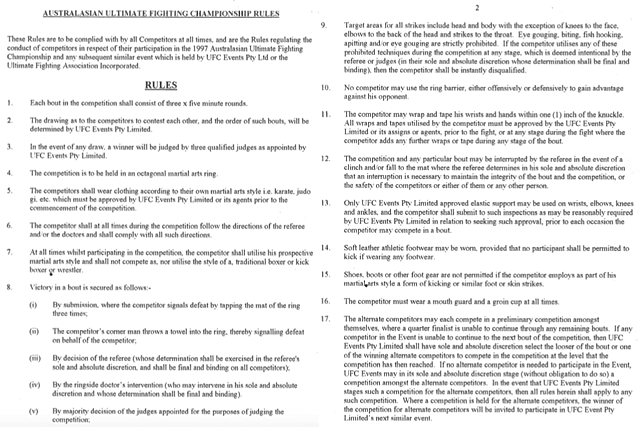

With the benefit of hindsight, the foundation that Bable built was many years ahead of its time. In addition to fighter contracts with lengthy clauses dealing with intellectual property, there were options Bable could exercise over the tournament winner to compete in subsequent events and a requirement that fighters would conduct themselves “with due respect to social conventions and public morals and decency.” Bable also created a separate governing body—the “Ultimate Fighting Association”—to provide the veneer of independent regulation. Moreover, he claims to have sold the distribution rights to Lion’s Gate and Warner Brothers, with plans on releasing one VHS focusing on the NHB tournament and another focusing on the exotic dance troupe, the “Fever Girls,” who were slated to stage choreographed performances in between bouts.

“What I was focused on was building everything from the bottom level so we could build higher,” Bable said. “I thought the first one would be a wash. It wouldn’t make money, but I wouldn’t lose money. But I would produce it to a level and have it so professionally done that we could then take that as a stepping point to go on to the next one. If you’re going to build business infrastructure, you need a big wide foundation. That’s what I was focused on: building everything from the bottom level so we could build higher.”

Everything hinged on making March 22 a success.

“There was so much happening at the time,” Bable said. “The fighters were in town. The press was going on. We were still organizing the venues, just getting the venue together with all the chairs and stuff. There was just so much happening. There’s no one thing that I recall that stands out. I was running around trying to keep all this stuff together. That was the main thing. It was organized chaos. Trying to keep the positive spin with the press and everything … the one thing that really impressed me the whole time was the professionalism and respect of the fighters that we had. All of them, they represented themselves, their trainers, the sport so well.

“Everyone was flying by the seat of their pants,” he added. “We were making it up as we were going along. I relied on some people, and everybody stepped up. Everybody I brought in really did their part.”

Meanwhile, in the background, Bable’s trademark lawyers were bobbing and weaving SEG’s cease-and-desist letters and injunction threats. In addition, the UFA “sanctioning body” continued its talks with the state boxing authority, which made a late-notice request that the fighters wear gloves.

* * *

For the cadre of fighters Bable relied on, much of the backstage maneuvering was beyond their field of vision. Some heard rumblings about SEG trying to stop the event or were aware of the boxing authority snooping around, but their focus was elsewhere—namely, the fights themselves.

“That’s when the nerves start, when you start to see your opponents,” Haseman said, remembering how he felt when meeting his fellow tournament participants during fight week. “Back then, it was just being tough. You roll up and you try to portray that level of toughness to the person you’re fighting. I’m a big believer that most fights are won in the dressing room before the bell. Certainly, that was the case with me.”

Experiencing his first-ever NHB fight week, Rocca was the lightest and youngest of the tournament participants. He similarly focused on remaining cool-headed.

“My general observation was that the seasoned veterans were calm and composed,” he said. “Myself, I did my best to be composed, but there was a lot of excitement. It’s kind of hard not to think ‘What the hell did I get myself into?’ when you’re standing next to Zane Frazier and Mario Sperry, but I had faith in my trainers, my teammates, in the techniques. I was ready to get after it.”

Fighters remember that the final bracket was decided by Bable towards the end of fight week. Because two pairs of fighters were teammates—Rocca and White from the Lion’s Den, and Te Rangi and Sweet from the Thunder Legs dojo in South Australia—a random draw was out of the question, so the lineup was calibrated to ensure that the only scenario in which teammates could fight was in the championship final.

Before anyone would get the chance, participants were left to their own devices to pass the time in the days leading up to the fights. Sperry recalls playing a relaxed game of pick-up basketball with Vernon White and other fighters. Shamrock fondly remembers shooting hoops with Sperry and his Brazilian posse and said that he joined White and Rocca on the beach most of the time.

“There were so many women [on Bondi Beach], and it was so much fun. I think that that was a really huge distraction to the guys, myself as well,” Shamrock said. “You know, they were really supposed to be focusing on the matches, and every day on the beach, we were hanging out with girls. I think that may have taken some of the legs out of Vernon.”

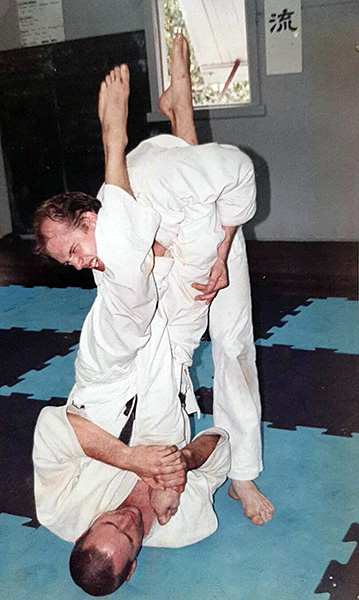

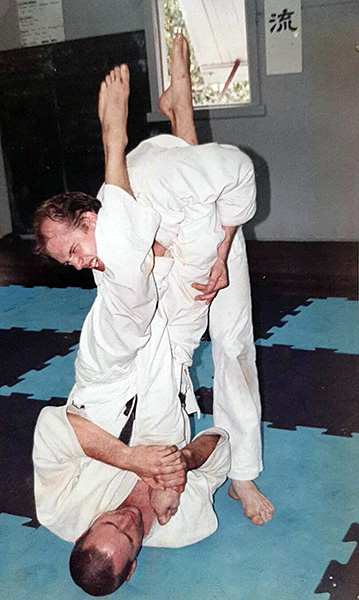

Iain Wright demonstrates an armbar on

Neil Bodycote for the camera.

One tournament participant who missed out on fight

week camaraderie was Neil Bodycote, a Goju Ryu karate and

submission fighting practitioner who was called up to compete on

approximately two days’ notice after Frazier pulled out. Bodycote

had put in an expression of interest for the event after seeing it

advertised in Blitz magazine several months prior, but his

application had been rejected, prompting him to ease up on his

training. Bable then approached him about being an alternate

roughly two weeks before the event. He would not compete in any

undercard bout but would be a fill-in if a finalist got injured. He

jumped back into training.

“I remember swearing a lot, and saying ‘I wish we’d known earlier,’” said Iain Wright, Bodycote’s coach and training partner, who would be one of his cornermen on fight night. “We had to run around and get out of work. I was excited for him. He was over the moon, with a little bit of trepidation in the sense that he wasn’t ready and hadn’t kept his training up. We were 150% enthusiasm, 5% skill. We weren’t overly prepared. I remember I was to pack the bags, and I left the f------ Vaseline on the kitchen table.”

The fighters arrived and were led backstage where they could warm up. In the adjacent room, the “Fever Girls” dance troupe were doing the same as a live band, “The Firm,” went through a sound check. Workers contracted to set up the custom-made octagon were underneath the structure, frantically installing insulation.

Still unresolved was whether the boxing authority would actually let the event go ahead. Bable, mic’d up and glued to his run sheet, was summoned to meet with a number of state-appointed commissioners. With them were between 20 and 40 uniformed officers and Bable’s lawyer animatedly pointing to a fighter contract, under which tournament participants had warranted that they were not a “prescribed boxer, kickboxer [or] wrestler” (which were regulated by the boxing authority) and submitted to the rules of the UFA “governing body.”

Even then, the boxing authority would not budge, refusing to give the greenlight as thousands of fans streamed into the venue and took their seats. Thinking on his feet, Bable changed the running order of the fights, swapping the first and second fights in the bracket so that Sperry and White, whom Bable hoped would spend most of their time ground fighting rather than striking, were now set to compete in the opening bout.

The lights went down, and standing in the octagon were the eight competitors, eyeballing one another from their respective portions of the chain-link fence. Ring announcer Dominic Bianco stepped into the cage to make the introductions and get the show underway.

“This was a huge moment for Australian martial arts,” Michael Schiavello said via email. “NHB was something we’d only ever read about in magazines or seen on old VHS tapes. For it to come to Australia and to see that cage for the first time was crazy.”

“It was like the Thunderdome,” Rocca said. “The people just wanted to see the action unfold.”

Bable crossed his fingers and took a big, deep breath.

Continue Reading » Part 4: History in the Making

Advertisement

BARBARIANS AT THE GATE

“The rules are there are no rules,” declared Sydney’s Daily Telegraph. “Today some of the world’s best exponents of kung fu, karate, jiu-jitsu and other martial arts disciplines will enter the octagonal cage to decide who is the ‘ultimate fighter.’”

The article went on to contradict its introduction by listing the

rules in the next paragraph: “Eight fighters, including the

Brazilian national champion Mario Sperry,

America’s Vernon ‘Tiger’

White and Canada’s Matthew Rocca,

will compete in the single elimination martial arts event with the

winner taking a $25,000 purse.”

The image adorning the article exhibited an airborne Elvis Sinosic, who would make his NHB debut at the tournament, landing a sidekick on a stationary punching bag. Beneath his picture, the article listed Sperry’s record as 273-1. The Telegraph was not the only outlet to send an unassuming reporter to the center of Sydney to report back on the planned “ultimate fighting” tournament, the first of its kind in Oceania. The previous evening, it was given lengthy coverage on ABC Radio National’s “The Sports Factor,” which tried in earnest to explore the appeal of NHB while also featuring the by-now staple critic who equated ultimate fighting with the decline of modern civilization.

Alongside sound bites from a traditionalist karate instructor concerned with the “corruption” of martial arts principles and MMA exponents Frank Shamrock and Carlson Gracie Sr., who spoke to the history and evolution of NHB, American sports sociologist Don Sabo was given lengthy airtime. He used it to compare fighters to prostitutes and claim that NHB events acted “as a type of cultural gasoline” that “fan the flames of male aggression.”

“The first Australasian Ultimate Fighting championships kicks and head butts its way into Sydney tomorrow night,” concluded presenter Amanda Smith. “I think I might be washing my hair at that time.”

For first-time fight promoter Randy Bable, the tournament was far from a sure thing, even as the days leading up the event turned to hours.

One of the main draws in the bracket, enormous kickboxer Zane Frazier, who competed at UFC 1 and UFC 9, pulled out after tearing his calf muscle running on Bondi Beach. His replacement, self-taught grappler Neil Bodycote, had to scramble to get his shift working security at a Newcastle nightclub covered.

There was also the presence of the New South Wales Boxing Authority, which had not given its blessing for the event to move forward and would send a small battalion of uniformed police officers down to the harbor, ready to shut down the spectacle if the state-appointed commissioners did not like what they saw.

Plus, New York’s Semaphore Entertainment Group, which owned and operated the Ultimate Fighting Championship, threatened to go to court and seek an injunction shutting down the event on the grounds that Bable was infringing its trademarks and passing itself off as the UFC.

On top of all that, the faux octagon had not been properly reinforced, prompting fears that the fighters would fall through the canvas if last-minute modifications were not made.

“It was insane,” a grinning Bable recounted 24 years later. “It was crazy.”

Future UFC champion Frank Shamrock, one of the many historically significant MMA figures to be pulled into the orbit of Australia’s first-ever NHB show, knew this was not actually a UFC event, and he had questions.

“I was wondering how they were using the name and stuff,” Shamrock said, “but at the time, I was really just focusing on fighting and training. I was just excited to go to Australia and for the guys to compete. There was a good prize. It was one of those trips that I really enjoyed and was really looking forward to.”

As the head coach of the famed Lion’s Den, Shamrock put up Pancrase stalwart Vernon White and untested Matt Rocca as event participants. It was Shamrock’s job to oversee their preparation as well as corner the pair in Sydney. The role came with its share of perks, including staying at the Swiss Grand Hotel on Bondi Beach through fight week. The former King of Pancrase was well-received by the martial arts community, which came out in force for the tournament.

The event itself was preceded by approximately two months training at the Lion’s Den academy in Lodi, California, a precursor to today’s MMA super camps. The Lion’s Den model provided fighters with training, housing and meals in exchange for a cut of their earnings. With Ken Shamrock away making the transition to professional wrestling, the job of running the fight team fell largely to Frank.

“I didn’t have a lot of no holds barred experience at the time,” he said. “Back then, we had no information on anybody. Ken would send me into the dressing rooms of people competing. I would look at their outfits and listen to what they were saying. That was what our research was. It was so rudimentary it was ridiculous.”

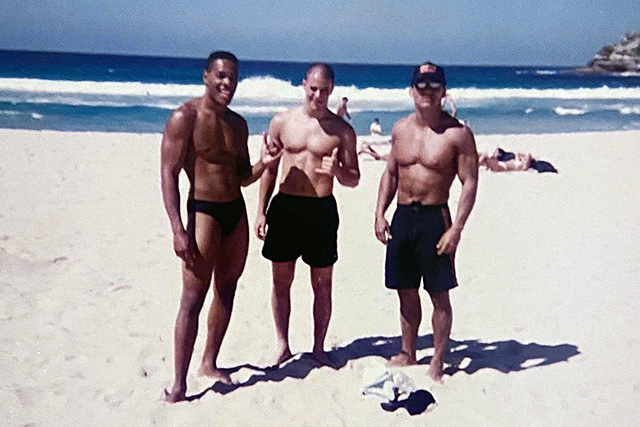

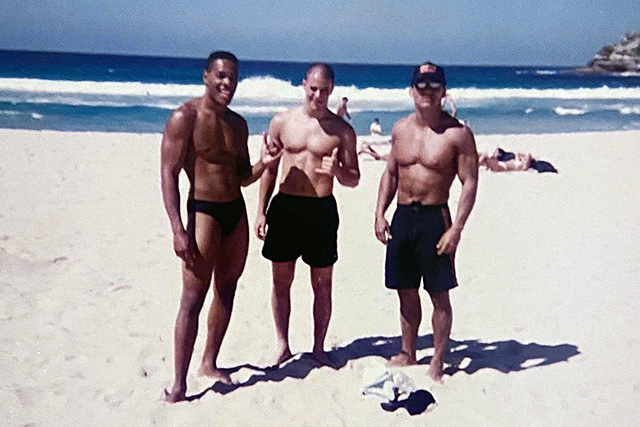

Vernon White, Matt Rocca and Frank Shamrock catching some rays

at Bondi Beach prior to the tournament. | Photo Courtesy: Matt

Rocca

Frank had high hopes for White, a fellow Pancrase competitor who was the second person inducted into the Lion’s Den stable in 1993. White was coming off of a finals appearance against Pedro Rizzo in an eight-man World Vale Tudo Championships tournament, and after three years as a pro fighter, he had claimed a deceiving 10-18-1 record, most of which fell under Pancrase’s modified rules in Japan. Having witnessed Australian fighters’ limited ground game on the Pancrase circuit, Shamrock figured White would easily outgrapple the locals or have the striking prowess needed to put out anyone on the feet.

The main focus of the fight camp in early 1997 was transitioning from open-hand strikes and rope escapes to the much less prescriptive world of NHB in a cage.

“We went from fighting in Pancrase to doing straight-out MMA, so in training, we couldn’t lay on our backs; you had to move, unless you wanted to get punched in the face,” White remembered. “Pancrase was way different. There was no punching in the face, open-hand only, unless somebody really pissed you off. Once we got into this, into MMA and NHB, there was no more making faces. You’d get your eyebrows punched off.”

Whereas White was an experienced competitor for the era, Rocca, his 20-year-old counterpart, was less than a year into his tenure at the Lion’s Den. Rocca carried the badge of “young boy,” a term denoting an entry-level position in the academy’s pecking order, with responsibility over the Den’s house chores.

“So much time is spent [in the Lion’s Den] trying to earn your stripes,” Rocca said. “You’re a young boy. You’re shaving your head. You’re taking on all of the menial tasks: washing, cleaning, groceries. There was this symbolism. You get the opportunity to cross over and become a fighter. I just wanted to seize the opportunity. I knew that going into the event there was going to be people in there with a lot more experience than me—in martial arts and also in life. I was 20 years old, and everything was going a million miles a minute.”

Originally signed as an alternate with a single bout on the undercard, Rocca was bumped up to the main bracket due to a succession of withdrawals. He was far from the only combatant who would make his debut that night. Of the five ANZACs on the card—Elvis Sinosic, Chris Haseman and Neil Bodycote hailed from different parts of Australia, while Hiriwa Te Rangi and Simon Sweet were kickboxers from New Zealand—only Haseman had NHB experience in the one-and-done “Martial Arts Reality Superfighting” event in Alabama the previous November.

Sperry also competed in the MARS event, taking home the MARS Superfight Championship, rightfully making him, White and Haseman the tournament favorites for people in the know.

In part, the Oceanic-centric nature of the roster was attributable to the withdrawal of UFC veterans Gerry Harris, Steve Jennum and Zane Frazier from the tournament, prompting Bable to call up each of his three alternates—Rocca, Sinosic and Bodycote—to the main bracket.

“There were people who knew what they were doing, and there were people who didn’t,” said Mark Castagnini, who commentated the event and was involved in promoting it through Blitz martial arts magazine, which he managed. Australian and New Zealand fighters “just wanted to test themselves against the best,” he continued. “Today, nobody fights in the UFC or gets into the cage unless they’re 100% ready. They’ve got high-performance coaching; they’ve got all of this knowledge. These blokes had nothing. They were just getting in there, seeing the bloke across from then and having a crack, hoping it would work out.”

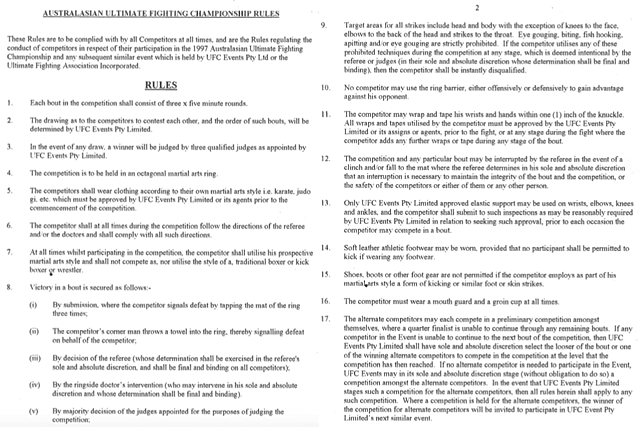

An

early draft of the rules, annexed to Matt Rocca’s contract. |

Provided by Matt Rocca

The lineup was also impacted by the reluctance of some of Australia’s more experienced NHB exports, including Pancrase’s Larry Papadopoulos and Alex Cook, to take a risk on a new promotion.

“We were approached and asked if we wanted to fight,” said Papadopoulos, the most successful Australian who competed for the Japanese organization at the time. “Because we were kind of contracted with Pancrase, we asked the promotion if they were OK with it. After some hemming and hawing the Japanese promoters regarded us as their talent, so they asked us not to fight. It was something where it was an unproven promoter. We didn’t really know whether the event would take off, and therefore, we kind of held back. We said ‘not this one,’ and thought we’d see how it goes. That’s why I didn’t personally get involved.”

The circumspection of Papadopoulos, who would come to be involved in the event as a consultant to Bable and a cornerman to Bodycote, was apparently shared by many of Australia’s other big names in combat sports. Efforts to secure Adam Watt, at that time one of the country’s most highly regarded kickboxers, came to nothing. Similar approaches to eight-time world kickboxing champion Stan “The Man” Longinidis were apparently rebuffed on the understanding that conversations could resume if and when Bable geared up for the second tournament, then slated for October 1997.

Elite fighters were not the only people doing due diligence from the bleachers. According to Bable, the late Rene Rivkin, a famous Australian stockbroker who was convicted on insider trading charges in 2003, may have been interested in investing in the NHB startup. Rivkin had his assistant call looking to secure front-row seats a few days before the debut event. Bable tried and failed to land sponsors or investors in the early stages of setting up the tournament, and he rebuffed Rivkin’s request, saying the seats were sold-out while believing there would be opportunities to court investors after pulling off the event.

With the benefit of hindsight, the foundation that Bable built was many years ahead of its time. In addition to fighter contracts with lengthy clauses dealing with intellectual property, there were options Bable could exercise over the tournament winner to compete in subsequent events and a requirement that fighters would conduct themselves “with due respect to social conventions and public morals and decency.” Bable also created a separate governing body—the “Ultimate Fighting Association”—to provide the veneer of independent regulation. Moreover, he claims to have sold the distribution rights to Lion’s Gate and Warner Brothers, with plans on releasing one VHS focusing on the NHB tournament and another focusing on the exotic dance troupe, the “Fever Girls,” who were slated to stage choreographed performances in between bouts.

“What I was focused on was building everything from the bottom level so we could build higher,” Bable said. “I thought the first one would be a wash. It wouldn’t make money, but I wouldn’t lose money. But I would produce it to a level and have it so professionally done that we could then take that as a stepping point to go on to the next one. If you’re going to build business infrastructure, you need a big wide foundation. That’s what I was focused on: building everything from the bottom level so we could build higher.”

Everything hinged on making March 22 a success.

“There was so much happening at the time,” Bable said. “The fighters were in town. The press was going on. We were still organizing the venues, just getting the venue together with all the chairs and stuff. There was just so much happening. There’s no one thing that I recall that stands out. I was running around trying to keep all this stuff together. That was the main thing. It was organized chaos. Trying to keep the positive spin with the press and everything … the one thing that really impressed me the whole time was the professionalism and respect of the fighters that we had. All of them, they represented themselves, their trainers, the sport so well.

“Everyone was flying by the seat of their pants,” he added. “We were making it up as we were going along. I relied on some people, and everybody stepped up. Everybody I brought in really did their part.”

Meanwhile, in the background, Bable’s trademark lawyers were bobbing and weaving SEG’s cease-and-desist letters and injunction threats. In addition, the UFA “sanctioning body” continued its talks with the state boxing authority, which made a late-notice request that the fighters wear gloves.

For the cadre of fighters Bable relied on, much of the backstage maneuvering was beyond their field of vision. Some heard rumblings about SEG trying to stop the event or were aware of the boxing authority snooping around, but their focus was elsewhere—namely, the fights themselves.

“That’s when the nerves start, when you start to see your opponents,” Haseman said, remembering how he felt when meeting his fellow tournament participants during fight week. “Back then, it was just being tough. You roll up and you try to portray that level of toughness to the person you’re fighting. I’m a big believer that most fights are won in the dressing room before the bell. Certainly, that was the case with me.”

Experiencing his first-ever NHB fight week, Rocca was the lightest and youngest of the tournament participants. He similarly focused on remaining cool-headed.

“My general observation was that the seasoned veterans were calm and composed,” he said. “Myself, I did my best to be composed, but there was a lot of excitement. It’s kind of hard not to think ‘What the hell did I get myself into?’ when you’re standing next to Zane Frazier and Mario Sperry, but I had faith in my trainers, my teammates, in the techniques. I was ready to get after it.”

Fighters remember that the final bracket was decided by Bable towards the end of fight week. Because two pairs of fighters were teammates—Rocca and White from the Lion’s Den, and Te Rangi and Sweet from the Thunder Legs dojo in South Australia—a random draw was out of the question, so the lineup was calibrated to ensure that the only scenario in which teammates could fight was in the championship final.

Before anyone would get the chance, participants were left to their own devices to pass the time in the days leading up to the fights. Sperry recalls playing a relaxed game of pick-up basketball with Vernon White and other fighters. Shamrock fondly remembers shooting hoops with Sperry and his Brazilian posse and said that he joined White and Rocca on the beach most of the time.

“There were so many women [on Bondi Beach], and it was so much fun. I think that that was a really huge distraction to the guys, myself as well,” Shamrock said. “You know, they were really supposed to be focusing on the matches, and every day on the beach, we were hanging out with girls. I think that may have taken some of the legs out of Vernon.”

(+ Enlarge) | Photo Courtesy: Iain Wright

Iain Wright demonstrates an armbar on

Neil Bodycote for the camera.

“I remember swearing a lot, and saying ‘I wish we’d known earlier,’” said Iain Wright, Bodycote’s coach and training partner, who would be one of his cornermen on fight night. “We had to run around and get out of work. I was excited for him. He was over the moon, with a little bit of trepidation in the sense that he wasn’t ready and hadn’t kept his training up. We were 150% enthusiasm, 5% skill. We weren’t overly prepared. I remember I was to pack the bags, and I left the f------ Vaseline on the kitchen table.”

The fighters arrived and were led backstage where they could warm up. In the adjacent room, the “Fever Girls” dance troupe were doing the same as a live band, “The Firm,” went through a sound check. Workers contracted to set up the custom-made octagon were underneath the structure, frantically installing insulation.

Still unresolved was whether the boxing authority would actually let the event go ahead. Bable, mic’d up and glued to his run sheet, was summoned to meet with a number of state-appointed commissioners. With them were between 20 and 40 uniformed officers and Bable’s lawyer animatedly pointing to a fighter contract, under which tournament participants had warranted that they were not a “prescribed boxer, kickboxer [or] wrestler” (which were regulated by the boxing authority) and submitted to the rules of the UFA “governing body.”

Even then, the boxing authority would not budge, refusing to give the greenlight as thousands of fans streamed into the venue and took their seats. Thinking on his feet, Bable changed the running order of the fights, swapping the first and second fights in the bracket so that Sperry and White, whom Bable hoped would spend most of their time ground fighting rather than striking, were now set to compete in the opening bout.

The lights went down, and standing in the octagon were the eight competitors, eyeballing one another from their respective portions of the chain-link fence. Ring announcer Dominic Bianco stepped into the cage to make the introductions and get the show underway.

“This was a huge moment for Australian martial arts,” Michael Schiavello said via email. “NHB was something we’d only ever read about in magazines or seen on old VHS tapes. For it to come to Australia and to see that cage for the first time was crazy.”

“It was like the Thunderdome,” Rocca said. “The people just wanted to see the action unfold.”

Bable crossed his fingers and took a big, deep breath.

Continue Reading » Part 4: History in the Making

Related Articles