How a UFC Impostor Became Australia’s First NHB Event

This is the fourth installment of a multi-part series on the

first modern MMA show held in Australia, billed the “Australasian

Ultimate Fighting Championship.”

PROLOGUE |

PART 1 |

PART 2 |

PART 3 |

PART 4 |

PART 5

Opening an eight-man openweight tournament billed as the inaugural

“Australasian Ultimate Fighting Championship,” the first modern MMA

fight on Australian soil pit Mario Sperry

against Vernon

White.

Sperry’s entrance was a spectacle in itself and would have made all but the most ostentatious prizefighters jealous. He was led to the cage by a Brazilian carnival of drummers and costumed dancers flanked by the pioneering Carlson Gracie Sr. and future UFC middleweight champion Murilo Bustamante. Moments later, White made his walk. Understated by comparison, White wore a black gi and a menacing stare. “Tiger” slowly moved towards the octagon, with Frank Shamrock supporting as his lone cornerman.

“Randy instructed us, ‘When you talk about what your training is and who you’re representing, don’t mention boxing, wrestling or kickboxing,’” remembered tournament participant Elvis Sinosic. “He told us to mention a martial art—karate, judo, jiu-jitsu—and [to state] it is a martial arts tournament, not a boxing or kickboxing event. He was very specific on ensuring that we used the correct terminology when we discussed it in interviews and in the local magazines. Under the relevant legislation, [the authority] didn’t have jurisdiction to stop martial arts events.”

What relief Bable must have felt 10 seconds into the first bout. Sperry bull rushed White, clinched him against the fence, secured a takedown and then moved to mount. Thus began what commentator Michael Schiavello would later describe in Blitz magazine as the “War on the Floor”—one of the most technical and tactical cage fights for the era which went the full distance.

Over the course of 15 minutes, the gloved Sperry relentlessly hunted for submissions, periodically stunning White with ground-and-pound whenever he got into a dominant position. The lighter, scrappier “Tiger” escaped Sperry’s submission attempts between his own glimmers of offense, desperately trying to get the fight to the feet where he had the advantage.

As the fighters tied themselves up on the canvas, referee Cameron Quinn crawled next to them, capturing the minutiae of the contest on the lipstick camera mounted on his head. Schiavello dubbed it the “Cam Cam” on the VHS broadcast.

When the final bell sounded, there was little doubt that Sperry would be named the winner by the panel of cageside judges. The only controversy came at the conclusion of the first round, where Sperry refused to dismount White and return to his corner after the bell. A confused and frustrated White and an animated Quinn repeatedly instructed Sperry that the round was over and appealed to his corner to say the same. Eventually, the Brazilian did what he was told.

“I made a mistake,” Sperry recounted. “I tried to finish the fight as quickly as I could so that I can save energy, but man, I almost died. Luckily, it was the first fight of the show. I had a lot of time to rest because then the other fights happened.”

“A lot of people had told me that he was going to try and stand up with me because he wanted to prove his standup, but that was short-lived,” White said. “He was trying to take me down and keep me down throughout the whole match. What I remember most about the fight: him taking me down and me escaping and getting up, trying to run around his legs, grabbing his legs, moving them, trying to punch him.”

This, Bable said, had the effect he hoped it would.

“The police, they were ready to haul people out,” Bable said. “Then the event started and they saw [Sperry and White fighting] and they said, ‘This is fine, they’re hugging each other on the floor.’ Seriously. A couple of them actually stuck around. We let them into the VIP area.”

With the threat of state-sanctioned closure neutralized, the fights were finally able to proceed.

* * *

The opening round of the tournament was in the books and had achieved its most important purpose: Her Majesty’s finest did not storm the octagon to call off the tournament. Still, Sperry-White left the crowd restless. Many of the spectators were unable to fully see when the fight went to the canvas and some booed in frustration.

“This was before we had big screens up,” said Bain Stewart, a kickboxing promoter who managed tournament participant Chris Haseman and consulted Bable on the event. “It sort of fell a bit flat because people were trying to see the fights from a million miles away.”

Fans bayed for blood, and the second fight on the card promised to cater to their appetites. Auckland kickboxer and Zen Do Kai karate practitioner Simon Sweet faced everyman security guard Neil Bodycote, a self-taught grappler and Goju Ryu karate stylist called up to fight in the main tournament on late notice. Flanked by coach and training partner Iain Wright and Pancrase fighter Larry Papadopoulos, Bodycote made the walk looking slightly terrified. The thickly built Sweet followed with a traditional Maori haka, making him an imposing figure next to his balding, pot-bellied opponent.

Bodycote, the first Australian to fight in an Australian mixed martial arts event, met Sweet in the center of the cage with a flurry of punches and kicks, taking enormous punishment from the Kiwi to mount his own frenetic offense. After trying and failing to get the fight to the ground, Bodycote was hit by a hellacious roundhouse kick to the body followed by powerful hooks to the head. Sweet repeatedly used his bulk to thwart Bodycote’s takedown attempts and move into dominant positions from which he landed concussive ground-and-pound and a perfectly timed soccer kick. When they resumed on their feet, Sweet landed a Mark Hunt-esque jumping left hook followed by a right hook. Every law of physics dictates that Bodycote should have gone down, but he did not. Bodycote resumed an offensive position and threw punches, even though they seemed to possess one tenth the power of Sweet’s. The 5,000 strong crowd was on its feet and the cheers were deafening.

Eventually, Bodycote ended up in mount position after Sweet—a novice on the ground—attempted a sloppy guillotine. However, as Schiavello screamed on the VHS broadcast, Bodycote’s punches lacked the “mustard” necessary to get the fight stopped. He attempted an armbar and Sweet escaped, landing more punches and kicks on Bodycote as the round ended. Bodycote returned to his corner, nursing what would later be diagnosed by the ringside doctor as a broken jaw. “Forget Rocky!” screamed Mark Castagnini to Schiavello. “This man Neil Bodycote is the real thing.”

Neil Bodycote briefly turns the tables in the

first round of his fight with Simon Sweet.

The fighters came out for the second round, and Sweet once again

led the dance on the feet with punishing right hands. Both men were

visibly fatigued, but Sweet was still the predator and the scrappy

never-say-die Bodycote was still the prey. Suddenly, Bodycote

snatched a front headlock. Squeezing for his life, he took Sweet to

the floor. The Kiwi was too tired or too out of his depth on the

ground to defend and tapped out.

“To this day, Neil has more heart than any other fighter that I’ve ever seen,” Bable said. “The way he came out of that fight and won, from where he was at. Hands down, he needs to be recognized for that above all else.”

* * *

Whereas the first two fights of the event took a combined 21 minutes, the other half of the bracket featured a pair of fast finishes.

First up, Elvis Sinosic, 25, met Matt Rocca, 20, in a battle of amiable young guns. “The King of Rock N’ Rumble” opened the bout by landing heavy leg kicks on his Canadian adversary. Rocca, motivated to get the fight to the floor, attempted a shot and then pivoted to pull guard. Sinosic held Rocca’s left leg and secured a favorable position from which to ground-and-pound. He landed a series of hard straight rights to Rocca’s head, which bounced off the canvas. Almost immediately, the semiconscious Rocca started tapping the canvas. The fight was over in 41 seconds, and Sinosic exultantly strutted around the octagon, his hands raised in victory.

Next up was the stoic Chris “The Hammer” Haseman versus Commonwealth kickboxing champion and renowned nice guy Hiriwa Te Rangi. This fight, like many of its era, was defined by the former’s prowess on the ground and the latter’s lack thereof. In the training and interview footage featured in the VHS of the event, Te Rangi looked impressive, landing lethal kicks and punches on the pads. More than two decades later, Te Rangi’s feelings about stepping into the cage are slightly more candid.

“I’ve never felt nervous like that, just because I hadn’t done the groundwork for some years,” he said. “I was really out of my comfort zone.”

The fight commenced with Haseman, the only local with “no rules” experience, immediately clinching Te Rangi, throwing him to the canvas and maneuvering to mount. From there, he isolated the New Zealander’s head and dug his chin into Te Rangi’s eye, slowly increasing the pressure until a tapout came 55 seconds after the opening bell.

“Fighting him was simple,” Haseman said. “The only way I could lose that fight is getting punched, kicked or kneed. As soon as it went to the ground, it was up to me to lose, you know what I mean? When you’ve got someone on the ground, you’re ground-and-pounding, that head doesn’t have anywhere to go. You’re almost punching a rock. Breaking your hands was what you had to watch. That chin in the eye thing was my wrestling coach [Bill Turner]’s idea. He said, ‘I want to see you win the fight with this technique,’ and that’s what I did.”

Referee Cameron Quinn keenly remembered Haseman’s use of the chin-to-the-eye technique and the controversy it generated during and after the bout.

“It was a great technique, but I think it was really stretching the sportsmanship,” Quinn said. “You’d need a lawyer to determine what an eye gouge was. In the spirit of sportsmanship, though, it doesn’t take anything to determine. Everyone knows that an eye gouge is anything that puts pressure on or endangers another person’s eye.”

* * *

With the quarterfinal round in the books, Sperry, Bodycote, Sinosic and Haseman moved to the next stage. Consistent with Bable’s vision, there had been little dead time in between the fights. The exotic dance troupe Fever Girls performed three times and a band, The Firm, played Motown tunes at various points throughout the evening.

Prolific pulp comedy fiction writer Robert G Barrett, whose Les Norton series made him a literary celebrity Down Under, watched the fights play out from ringside. So enamored with what he saw that he included the event as a plot point in his 1998 book “Mud Crag Boogie.” Included along with his narration of the fights themselves, which are relayed accurately and without creative license, is the following passage, describing the burlesque nature of the intermission entertainment:

“If you were a people perv it was paradise; providing you kept your mouth shut and didn’t make too much eye contact. The band stopped, the lights faded momentarily and just as some heavy dance music started up five ninjas in black entered the ring and started kicking and punching, rolling and tumbling around. The lights dimmed momentarily again and the ninja gear came off to reveal five well-stacked, sexy blondes in G-strings who started wiggling their bums and shaking their boobs to the howls and roars of appreciation from the audience.”

Sperry was backstage at the time of these performances and memorably recalled watching the more provocative portions on VHS with his family back in Brazil.

“After six months, I got the tape,” he said. “I got my family to watch the fight: my mum, my dad, my wife, my friends, my fans. I put on the VHS, and man, I didn’t know. I didn’t know they had the show on the break. There were those girls with their tits hanging out kissing each other in bikinis. My wife was like, ‘Oh my god. What’s going on? What did you do here?’ I said, ‘I didn’t do anything. I was fighting.’”

* * *

Round 2 of the tournament, which piggybacked off some fortuitous matchmaking in the first round, featured all three of the Australian competitors. Sperry would meet Bodycote, who had been diagnosed by the ringside doctor with a broken jaw and was urged not to compete, and Sinosic was matched against Haseman.

The bout between Sperry and Bodycote lasted a merciful 49 seconds, with “Ze Mario” catching a lazy kick in the opening exchange and dumping his opponent on the ground. From there, he quickly secured Bodycote’s back and began landing punches to his head and jaw, forcing the local fighter to tap to strikes.

“As soon as Mario got on top of him, I threw the towel in, Neil started tapping and Cameron stopped it,” remarked Wright, who remains in awe of Bodycote trying his hand against Sperry despite a broken jaw.

Haseman’s fight with Sinosic would also be over within the opening five minutes, but it would prove to be one of the more competitive bouts of the evening. The much bigger Haseman sought to bully Sinosic on the ground, but Sinosic was prepared and fished for armbars and triangle chokes from the guard, generally matching the Queenslander’s pace and output. Eventually, Haseman achieved mount and once again resorted to putting his chin in Sinosic’s eye, extracting the submission 2:47 into Round 1. This prompted a brief exchange of raised voices between the referee and Sinosic’s corner, which protested the stoppage.

Chris Haseman towers over Elvis Sinosic in

their semifinal bout.

“Elvis didn’t like it too much,” Haseman said, “but I always say,

if I could do that to Elvis with my chin, imagine what I could do

with my fists; and he’s got to wear that. To be tapped by a chin,

you’ve really got to be under control. You just can’t put a chin in

someone’s eye. I had to have 100 percent control of the rest of you

to be able to put a chin in your eye, so it’s not as cheap as some

people thought.”

The final fight was set. Brazil’s Mario Sperry would face Australia’s Chris Haseman to determine the inaugural titleholder of the “Australasian Ultimate Fighting Championship.” Before their contest, a last-minute change to the rules was made banning Haseman’s chin-to-the-eye submission.

“When it came to the final, [Sperry] said to the promoter that he knew his value,” Quinn said. “He said, ‘I won’t fight this final unless that technique is not allowed. This will not go unless the chin pressure is removed. It’s against the spirit.’ I was there for this conversation in the change rooms. And so, we approached Chris and Bill [Turner] and informed them that the technique was out. In a way, they almost expected it would have been removed earlier. It was like they’d been shoplifting and had gotten busted.”

Bable and Haseman’s version of events align with Quinn’s. For his part, Haseman does not believe it would have made any difference.

“That chin in the eye submission requires complete control and dominance, and Mario was way too good to allow me to dominate him on the ground and give me that capability,” he said. “The removal of the technique says more about Mario than it says about me. We were surprised that that’s what he thought he had to do in order to better position him for the win. If it was me, I wouldn’t have given a s---.”

Sperry had no recollection of this development.

“If it happened,” he said, “I don’t remember, or nobody told me about it.”

With 17 minutes of fight time under his belt, Sperry should have been more fatigued than Haseman, whose total fight time was less than four minutes. You would not know it from the footage of their walkouts. Before the tournament final, a sublimely confident Sperry calmly made the walk with a look of bemusement on his face as he climbed into the octagon. “The Hammer,” preceded by aboriginal dancers bearing spears and covered in war paint, wore a look that could kill.

Like many of the bouts in the tournament, the final was over fast. Sperry quickly closed the distance. Though he sustained a cut from a clash of heads, Sperry managed to wrap up Haseman and take him to the ground. From mount, he landed punches and applied what looked to be an attempted eye gouge with his thumb before Quinn, having seen enough, stopped the contest and declared Sperry the winner by technical knockout after 72 seconds.

Some minutes later, the Brazilian was presented with a novelty check and a belt emblazoned with the words “Ultimate Fighting Championship.” Bable stood in the octagon, beaming. The first leg of the journey towards bringing the no holds barred “revolution” to Australia was off to a flying start.

Next came the crash landing.

Finish Reading » Afterglow and Unrealized Potential

Advertisement

HISTORY IN THE MAKING

Sperry’s entrance was a spectacle in itself and would have made all but the most ostentatious prizefighters jealous. He was led to the cage by a Brazilian carnival of drummers and costumed dancers flanked by the pioneering Carlson Gracie Sr. and future UFC middleweight champion Murilo Bustamante. Moments later, White made his walk. Understated by comparison, White wore a black gi and a menacing stare. “Tiger” slowly moved towards the octagon, with Frank Shamrock supporting as his lone cornerman.

By placing White and “Ze Mario” as the opening fight on the card,

Randy Bable banked on the fight playing out mainly on the ground.

With members of the New South Wales Boxing Authority on scene

alongside a small army of uniformed police officers who threatened

to shut down the event if the commissioners did not like what they

saw, Bable desperately hoped the bout would not be construed as an

unsanctioned boxing or kickboxing match, which would have triggered

the authority’s jurisdiction. As further insurance, Bable

repeatedly directed the fighters to identify with their martial

arts disciplines in interviews and avoid any suggestion that they

were engaging or even training in sports regulated by the

authority.

“Randy instructed us, ‘When you talk about what your training is and who you’re representing, don’t mention boxing, wrestling or kickboxing,’” remembered tournament participant Elvis Sinosic. “He told us to mention a martial art—karate, judo, jiu-jitsu—and [to state] it is a martial arts tournament, not a boxing or kickboxing event. He was very specific on ensuring that we used the correct terminology when we discussed it in interviews and in the local magazines. Under the relevant legislation, [the authority] didn’t have jurisdiction to stop martial arts events.”

What relief Bable must have felt 10 seconds into the first bout. Sperry bull rushed White, clinched him against the fence, secured a takedown and then moved to mount. Thus began what commentator Michael Schiavello would later describe in Blitz magazine as the “War on the Floor”—one of the most technical and tactical cage fights for the era which went the full distance.

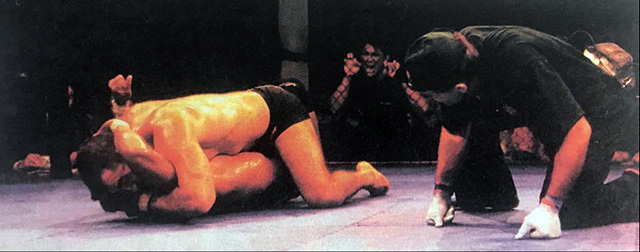

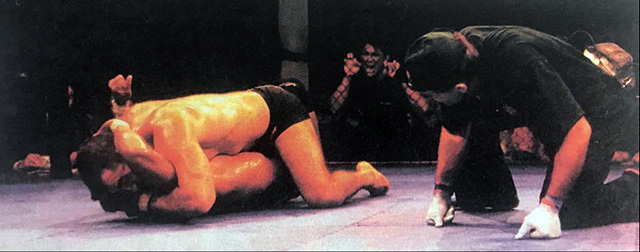

Mario Sperry and Vernon White in the “War on the Floor,” with

referee Cameron Quinn (and his mounted camera) watching closely

from the sidelines. From Blitz Magazine, Volume 11 (Issue

5).

Over the course of 15 minutes, the gloved Sperry relentlessly hunted for submissions, periodically stunning White with ground-and-pound whenever he got into a dominant position. The lighter, scrappier “Tiger” escaped Sperry’s submission attempts between his own glimmers of offense, desperately trying to get the fight to the feet where he had the advantage.

As the fighters tied themselves up on the canvas, referee Cameron Quinn crawled next to them, capturing the minutiae of the contest on the lipstick camera mounted on his head. Schiavello dubbed it the “Cam Cam” on the VHS broadcast.

When the final bell sounded, there was little doubt that Sperry would be named the winner by the panel of cageside judges. The only controversy came at the conclusion of the first round, where Sperry refused to dismount White and return to his corner after the bell. A confused and frustrated White and an animated Quinn repeatedly instructed Sperry that the round was over and appealed to his corner to say the same. Eventually, the Brazilian did what he was told.

“I made a mistake,” Sperry recounted. “I tried to finish the fight as quickly as I could so that I can save energy, but man, I almost died. Luckily, it was the first fight of the show. I had a lot of time to rest because then the other fights happened.”

“A lot of people had told me that he was going to try and stand up with me because he wanted to prove his standup, but that was short-lived,” White said. “He was trying to take me down and keep me down throughout the whole match. What I remember most about the fight: him taking me down and me escaping and getting up, trying to run around his legs, grabbing his legs, moving them, trying to punch him.”

This, Bable said, had the effect he hoped it would.

“The police, they were ready to haul people out,” Bable said. “Then the event started and they saw [Sperry and White fighting] and they said, ‘This is fine, they’re hugging each other on the floor.’ Seriously. A couple of them actually stuck around. We let them into the VIP area.”

With the threat of state-sanctioned closure neutralized, the fights were finally able to proceed.

The opening round of the tournament was in the books and had achieved its most important purpose: Her Majesty’s finest did not storm the octagon to call off the tournament. Still, Sperry-White left the crowd restless. Many of the spectators were unable to fully see when the fight went to the canvas and some booed in frustration.

“This was before we had big screens up,” said Bain Stewart, a kickboxing promoter who managed tournament participant Chris Haseman and consulted Bable on the event. “It sort of fell a bit flat because people were trying to see the fights from a million miles away.”

Fans bayed for blood, and the second fight on the card promised to cater to their appetites. Auckland kickboxer and Zen Do Kai karate practitioner Simon Sweet faced everyman security guard Neil Bodycote, a self-taught grappler and Goju Ryu karate stylist called up to fight in the main tournament on late notice. Flanked by coach and training partner Iain Wright and Pancrase fighter Larry Papadopoulos, Bodycote made the walk looking slightly terrified. The thickly built Sweet followed with a traditional Maori haka, making him an imposing figure next to his balding, pot-bellied opponent.

Bodycote, the first Australian to fight in an Australian mixed martial arts event, met Sweet in the center of the cage with a flurry of punches and kicks, taking enormous punishment from the Kiwi to mount his own frenetic offense. After trying and failing to get the fight to the ground, Bodycote was hit by a hellacious roundhouse kick to the body followed by powerful hooks to the head. Sweet repeatedly used his bulk to thwart Bodycote’s takedown attempts and move into dominant positions from which he landed concussive ground-and-pound and a perfectly timed soccer kick. When they resumed on their feet, Sweet landed a Mark Hunt-esque jumping left hook followed by a right hook. Every law of physics dictates that Bodycote should have gone down, but he did not. Bodycote resumed an offensive position and threw punches, even though they seemed to possess one tenth the power of Sweet’s. The 5,000 strong crowd was on its feet and the cheers were deafening.

Eventually, Bodycote ended up in mount position after Sweet—a novice on the ground—attempted a sloppy guillotine. However, as Schiavello screamed on the VHS broadcast, Bodycote’s punches lacked the “mustard” necessary to get the fight stopped. He attempted an armbar and Sweet escaped, landing more punches and kicks on Bodycote as the round ended. Bodycote returned to his corner, nursing what would later be diagnosed by the ringside doctor as a broken jaw. “Forget Rocky!” screamed Mark Castagnini to Schiavello. “This man Neil Bodycote is the real thing.”

(+ Enlarge) | Photo Courtesy: Iain Wright

Neil Bodycote briefly turns the tables in the

first round of his fight with Simon Sweet.

“To this day, Neil has more heart than any other fighter that I’ve ever seen,” Bable said. “The way he came out of that fight and won, from where he was at. Hands down, he needs to be recognized for that above all else.”

Whereas the first two fights of the event took a combined 21 minutes, the other half of the bracket featured a pair of fast finishes.

First up, Elvis Sinosic, 25, met Matt Rocca, 20, in a battle of amiable young guns. “The King of Rock N’ Rumble” opened the bout by landing heavy leg kicks on his Canadian adversary. Rocca, motivated to get the fight to the floor, attempted a shot and then pivoted to pull guard. Sinosic held Rocca’s left leg and secured a favorable position from which to ground-and-pound. He landed a series of hard straight rights to Rocca’s head, which bounced off the canvas. Almost immediately, the semiconscious Rocca started tapping the canvas. The fight was over in 41 seconds, and Sinosic exultantly strutted around the octagon, his hands raised in victory.

Next up was the stoic Chris “The Hammer” Haseman versus Commonwealth kickboxing champion and renowned nice guy Hiriwa Te Rangi. This fight, like many of its era, was defined by the former’s prowess on the ground and the latter’s lack thereof. In the training and interview footage featured in the VHS of the event, Te Rangi looked impressive, landing lethal kicks and punches on the pads. More than two decades later, Te Rangi’s feelings about stepping into the cage are slightly more candid.

“I’ve never felt nervous like that, just because I hadn’t done the groundwork for some years,” he said. “I was really out of my comfort zone.”

The fight commenced with Haseman, the only local with “no rules” experience, immediately clinching Te Rangi, throwing him to the canvas and maneuvering to mount. From there, he isolated the New Zealander’s head and dug his chin into Te Rangi’s eye, slowly increasing the pressure until a tapout came 55 seconds after the opening bell.

“Fighting him was simple,” Haseman said. “The only way I could lose that fight is getting punched, kicked or kneed. As soon as it went to the ground, it was up to me to lose, you know what I mean? When you’ve got someone on the ground, you’re ground-and-pounding, that head doesn’t have anywhere to go. You’re almost punching a rock. Breaking your hands was what you had to watch. That chin in the eye thing was my wrestling coach [Bill Turner]’s idea. He said, ‘I want to see you win the fight with this technique,’ and that’s what I did.”

Referee Cameron Quinn keenly remembered Haseman’s use of the chin-to-the-eye technique and the controversy it generated during and after the bout.

“It was a great technique, but I think it was really stretching the sportsmanship,” Quinn said. “You’d need a lawyer to determine what an eye gouge was. In the spirit of sportsmanship, though, it doesn’t take anything to determine. Everyone knows that an eye gouge is anything that puts pressure on or endangers another person’s eye.”

With the quarterfinal round in the books, Sperry, Bodycote, Sinosic and Haseman moved to the next stage. Consistent with Bable’s vision, there had been little dead time in between the fights. The exotic dance troupe Fever Girls performed three times and a band, The Firm, played Motown tunes at various points throughout the evening.

Prolific pulp comedy fiction writer Robert G Barrett, whose Les Norton series made him a literary celebrity Down Under, watched the fights play out from ringside. So enamored with what he saw that he included the event as a plot point in his 1998 book “Mud Crag Boogie.” Included along with his narration of the fights themselves, which are relayed accurately and without creative license, is the following passage, describing the burlesque nature of the intermission entertainment:

“If you were a people perv it was paradise; providing you kept your mouth shut and didn’t make too much eye contact. The band stopped, the lights faded momentarily and just as some heavy dance music started up five ninjas in black entered the ring and started kicking and punching, rolling and tumbling around. The lights dimmed momentarily again and the ninja gear came off to reveal five well-stacked, sexy blondes in G-strings who started wiggling their bums and shaking their boobs to the howls and roars of appreciation from the audience.”

Sperry was backstage at the time of these performances and memorably recalled watching the more provocative portions on VHS with his family back in Brazil.

“After six months, I got the tape,” he said. “I got my family to watch the fight: my mum, my dad, my wife, my friends, my fans. I put on the VHS, and man, I didn’t know. I didn’t know they had the show on the break. There were those girls with their tits hanging out kissing each other in bikinis. My wife was like, ‘Oh my god. What’s going on? What did you do here?’ I said, ‘I didn’t do anything. I was fighting.’”

The

VHS of “Caged Combat 1” was recently uploaded onto YouTube.

Promoter Randy Bable left one of the three comments posted at the

time of writing: “Fantastic seeing my fighting event that I put

together over 20 years ago making its way online. Still arguably

the greatest live MMA event ever promoted, if I do say so myself.”

The other two comments point viewers to the more risqué sections of

the intra-fight entertainment].

Round 2 of the tournament, which piggybacked off some fortuitous matchmaking in the first round, featured all three of the Australian competitors. Sperry would meet Bodycote, who had been diagnosed by the ringside doctor with a broken jaw and was urged not to compete, and Sinosic was matched against Haseman.

The bout between Sperry and Bodycote lasted a merciful 49 seconds, with “Ze Mario” catching a lazy kick in the opening exchange and dumping his opponent on the ground. From there, he quickly secured Bodycote’s back and began landing punches to his head and jaw, forcing the local fighter to tap to strikes.

“As soon as Mario got on top of him, I threw the towel in, Neil started tapping and Cameron stopped it,” remarked Wright, who remains in awe of Bodycote trying his hand against Sperry despite a broken jaw.

Haseman’s fight with Sinosic would also be over within the opening five minutes, but it would prove to be one of the more competitive bouts of the evening. The much bigger Haseman sought to bully Sinosic on the ground, but Sinosic was prepared and fished for armbars and triangle chokes from the guard, generally matching the Queenslander’s pace and output. Eventually, Haseman achieved mount and once again resorted to putting his chin in Sinosic’s eye, extracting the submission 2:47 into Round 1. This prompted a brief exchange of raised voices between the referee and Sinosic’s corner, which protested the stoppage.

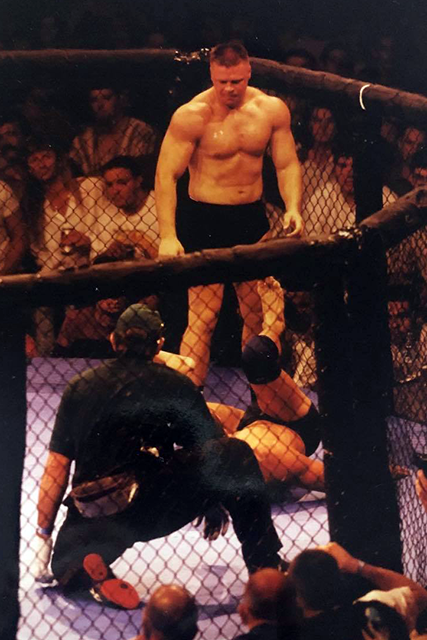

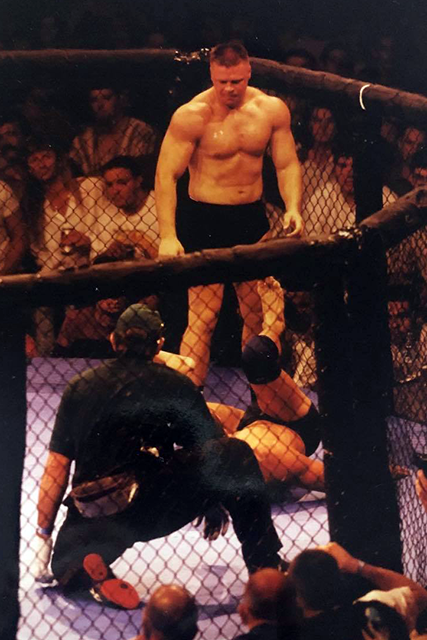

(+ Enlarge) | Photo Courtesy: Chris Haseman

Chris Haseman towers over Elvis Sinosic in

their semifinal bout.

The final fight was set. Brazil’s Mario Sperry would face Australia’s Chris Haseman to determine the inaugural titleholder of the “Australasian Ultimate Fighting Championship.” Before their contest, a last-minute change to the rules was made banning Haseman’s chin-to-the-eye submission.

“When it came to the final, [Sperry] said to the promoter that he knew his value,” Quinn said. “He said, ‘I won’t fight this final unless that technique is not allowed. This will not go unless the chin pressure is removed. It’s against the spirit.’ I was there for this conversation in the change rooms. And so, we approached Chris and Bill [Turner] and informed them that the technique was out. In a way, they almost expected it would have been removed earlier. It was like they’d been shoplifting and had gotten busted.”

Bable and Haseman’s version of events align with Quinn’s. For his part, Haseman does not believe it would have made any difference.

“That chin in the eye submission requires complete control and dominance, and Mario was way too good to allow me to dominate him on the ground and give me that capability,” he said. “The removal of the technique says more about Mario than it says about me. We were surprised that that’s what he thought he had to do in order to better position him for the win. If it was me, I wouldn’t have given a s---.”

Sperry had no recollection of this development.

“If it happened,” he said, “I don’t remember, or nobody told me about it.”

With 17 minutes of fight time under his belt, Sperry should have been more fatigued than Haseman, whose total fight time was less than four minutes. You would not know it from the footage of their walkouts. Before the tournament final, a sublimely confident Sperry calmly made the walk with a look of bemusement on his face as he climbed into the octagon. “The Hammer,” preceded by aboriginal dancers bearing spears and covered in war paint, wore a look that could kill.

Like many of the bouts in the tournament, the final was over fast. Sperry quickly closed the distance. Though he sustained a cut from a clash of heads, Sperry managed to wrap up Haseman and take him to the ground. From mount, he landed punches and applied what looked to be an attempted eye gouge with his thumb before Quinn, having seen enough, stopped the contest and declared Sperry the winner by technical knockout after 72 seconds.

Some minutes later, the Brazilian was presented with a novelty check and a belt emblazoned with the words “Ultimate Fighting Championship.” Bable stood in the octagon, beaming. The first leg of the journey towards bringing the no holds barred “revolution” to Australia was off to a flying start.

Next came the crash landing.

Finish Reading » Afterglow and Unrealized Potential

Related Articles